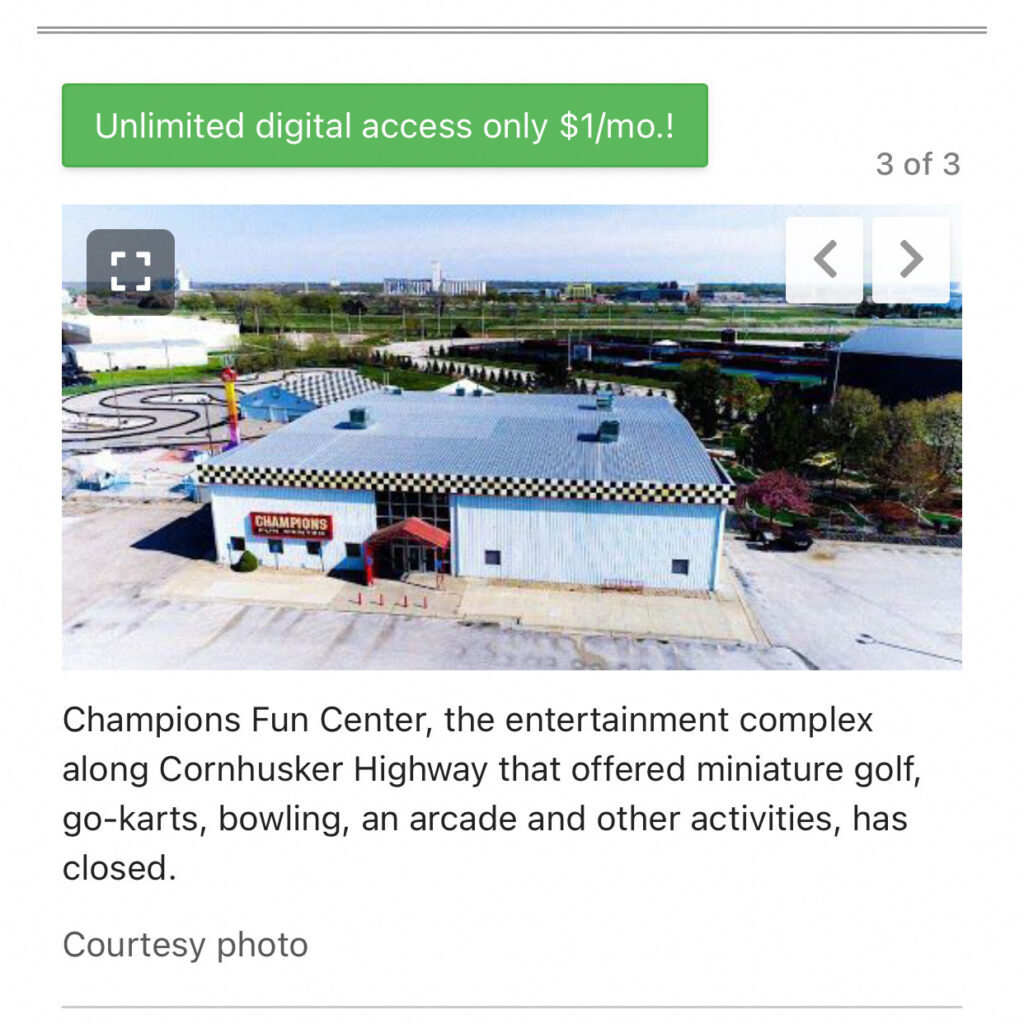

Champions Fun Center being reinvented into a place for young people to discover their untapped potential

by Margaret Reist Updated

Stanford Bradley Jr. looks for untapped potential.

In the kid at the emergency shelter who’s all wrapped up in Omaha’s gangs but knows he’s being given a chance and is trying to make it work.

In the young man at the detention center who needed a job and got one, then came every day to the auto detail shop Bradley and his dad own, got off probation and saved up enough money to buy a car.

In the story of hatching chicks, which Bradley cares much less about than the kid telling it, because he knows when he brings it up the next time they see each other that boy will know he means something to the grown-up with dreadlocks and the kind face.

And it’s what he sees in the 20,000 square feet of flashy arcade games and bowling lanes and empty birthday party rooms off Cornhusker Highway that was Champions Fun Center for the past two decades.

It has a new owner now — a Lincoln businessman named Tyler Irons, who saw potential there, too, as a home for the girls club basketball team he sponsors.

After Irons bought the building — and everything inside and out that drew kids there — he reached out to Bradley to help him turn it into a place for all kids.

“I see it in my head, how it’s going to work,” said Bradley, who named the youth advocacy nonprofit he started with his dad Untapped Potential. “I was so excited when Tyler reached out to me, when we started planning.”

Irons graduated from Lincoln East High School in 2007, joined the military, then dabbled in real estate and the car business after a medical discharge. He started a real estate tech company called VRLY in 2017.

About a year earlier he’d started something else: a girls basketball team that his then 5-year-old daughter Kaytee Irons, his niece and their friends asked if he’d sponsor. He did and both his business and the basketball organization took off.

“Then there were two teams, then four, then five,” he said. “You meet all these girls, you learn their stories, you get attached, then there’s more of them. It got to the point we felt we could have a bigger reach if we had bigger facilities.”

Then, by chance, one of his clients mentioned that Champions was for sale.

After he bought the building, Irons called everybody he could think of to help him get it off the ground, including Bradley, who he’d met years earlier when Bradley was coaching a small fry basketball team at the Salvation Army and asked if Irons’ daughter wanted to be on the team.

It’s still a work in progress, but Irons plans to remove the bowling alley and unearth the gym floor underneath for the basketball teams.

Tommy Johnson, who was just named girls basketball coach at North Star High, will continue as director of the VRLY Storm club.

Irons is in the process of getting the program approved so families can use child care subsidies for their children to buy a membership and attend an after-school program, and he hopes to continue to hold events there.

Bradley, who is associate director of team development at the Malone Center, will make it the base for his nonprofit work, help host events and create more programming.

“This is a big stage for all of us,” Bradley said. “It gives us a base.”

That base is already taking shape as Club LNK, which now offers teen nights. For $5 kids can play all the games and bowl — something many of them couldn’t afford to do when it was Champions.

Organizers enlisted the help of a University of Nebraska-Lincoln fraternity to build a giant haunted maze upstairs and hosted a Halloween event for kids.

Bradley and Irons are dreaming much bigger, though, envisioning a space for kids to come after school and do homework or get help from tutors, using the games and go-karts and putt-putt golf as incentives to make regular strides in an achievement zone.

When they started the teen nights, Bradley said he was surprised by how many of the kids had never been bowling.

“So now, after school, kids achieve their goals if they want to bowl for free,” he said. “They can earn points to be eligible for a pizza night — so we can make that connection.”

Making connections is key, Bradley said, the idea Untapped Potential is built on.

“Every kid isn’t going to have the same recipe for success,” he said. “It’s why it’s important to have individual responses for each kid.”

Bradley runs a program at the Malone Center to help foster good relationships with young people and the police; and through his nonprofit he works with young people at the detention center, helps parents understand their rights and advocate for their children who receive special-education services in school, and tries to make sure the organizations that are supposed to help kids are doing that.

“There’s a group of kids that look like me getting lost in the shuffle,” he said.

He knows they don’t get the services they should — he’s seen it with the kids he helps, and through his own experiences.

When he was 15 he was charged with several felonies. A juvenile court judge took a chance, letting him out on house arrest.

As soon as he got out he went to the Malone Center, began a job that turned into a passion, and changed the trajectory of his life.

He was barely monitored on probation, he said, though he’d been scared enough in detention that he was determined not to go back.

His brother — just 10 months older — got in trouble, too, but needed more support. He didn’t get it, and ended up in prison.

What if someone had reached out, Bradley said, maybe tapped into his brother’s love of music, led him in a direction that resulted in better decisions?

“That’s why places like this are so important,” he said.

He hopes Club LNK can offer kids a safe place to hang out, around people who care and away from influences that fuel gun violence.

He sees what unconscious bias can do, like a call he got from a mom whose son was suspended for singing a rap song that adults in the room interpreted as threatening.

“The culture for people of color really isn’t present in a lot of places,” he said.

Sara Hoyle, Lancaster County Human Services Director, said Bradley offers that to kids.

“I think he brings lived experiences. He’s often the voice for youth. He’s young enough, he can still remember what it’s like,” she said. “He’s connected to the community we’re really trying to provide services to.”

Bradley wants to offer academic support and job fairs and a place to get to know the young people who walk through Club LNK’s doors.

“Sometimes they just need someone to invest their time,” Bradley said. “You get them to buy in by doing that. Then they’ll follow through.”

Irons said he wants space for his basketball program, but also to create a place for all kids — to expose them to ideas and hands-on, real-world opportunities they might not get in school. To help them understand how to succeed, to keep working at something they feel passionate about, to not be afraid to fail, to learn and push through and keep going.

They want to be a resource for other nonprofits that could use the meeting space they have, or want incentives for the kids they serve, to partner with them to do more for kids.

Right now, the teen nights are being run with volunteers — many of them from the Malone Center — and the men hope to build on that.

“I want to build that kind of relationship with the community,” Bradley said. “That’s what me, Tyler and Tommy envision going on here.”

Bradley believes there’s untapped potential in the community — people who can help but might not know how, some who are overlooked because they don’t have the education.

“I had to put in six years to get a seat at the table,” he said. He’s earning a degree online from Peru State, one class at a time. “If I waited till I got a college degree, I’d be 30.”

He wants to find those people — and help young people become leaders.

”I don’t just want to find those people, I want to make those people.”

He’s already started: bringing more than 200 young people to a Husker football game when the university offered free tickets, taking a group of kids to meet with the mayor to talk about what they wanted to see in a new police chief.

He saw what that did for those kids.

“If a kid gets that at 15, what are they going to be at 20?”

Bradley figures you either invest in young people now, or you’ll have to do it later — it’s why he, Irons and Johnson want to reinvent a longtime entertainment spot into something more.